High Crimes and Misdemeanors

MARK S. HAMM, PH.D.

“High Crimes and Misdemeanors”:

George W. Bush and the Sins of Abu Ghraib

The second pillar of peace and security in our world is the willingness of free nations, when the last resort arrives, to retain aggression and evil by force.

--George W. Bush

London, November 19, 2003

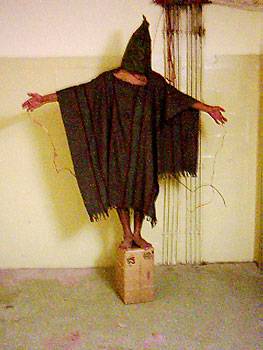

The chilling images of detainee abuse at Baghdad’s Abu Ghraib prison—especially the iconic figure of a hooded man connected to electrical wires; of Private Lynndie England posing in front of a line of naked men, cigarette dangling from her mouth, her finger pointed towards the genitals of naked victims—infuriated Muslims around the world and rallied Arab sentiment to the cause of Islamic extremism. Today copies of the photos can be seen in marketplaces from Egypt to thePhilippines, evoking the worst suspicions of Muslims everywhere: that Americans are corrupt, heartless, and hell-bent on humiliating Muslims and mocking their values. “If Osama bin Laden had hired a Madison Avenue public relations firm to rally Arabs’ hearts and minds to his cause,” observed one military researcher, “it’s hard to imagine that it could have devised a better propaganda campaign” (Carter, 2004:2).

Indeed, as if to remind the world that all terrorism begins with a grievance, four days after the Abu Ghraib photos were released the terrorist leader Abu Musab al-Zarqawi beheaded a 26-year-old Jewish businessman from Philadelphia named Nicholas Berg, and broadcast the gruesome event on an Islamic militant Web site, prefacing the decapitation with a statement about the torture scandal. Teenagers in Cairo, Bangkok, Karachi, and Cleveland—who had never even seen a convenience store robbery before—were suddenly able to download images of a black-clad terrorist hacking a man’s head off with a machete. More beheadings would follow, and like Berg they were all foreign victims wearing orange jumpsuits similar to Abu Ghraib prison garb. The message was clear: Not only had al-Qaeda in Iraq delivered a powerful symbolic protest against the brutality of U.S. torture, it had exacted its revenge in blood.

A nation that sanctions torture in defiance of its democratic principles pays a heavy price. The crimes of Abu Ghraib had devastating political consequences for theUnited States military adventure in Iraq. A U.S. government poll showed that Iraqi support for American forces plummeted from 63 percent to an abysmal 9 percent upon release of the Abu Ghraib images (McKelvey, 2007). But the problems had only begun. The torture scandal presaged a nationwide crime wave in Iraq(robberies, rapes, kidnappings, and carjacking) and aided the insurgency it was aiming to defeat by alienating large segments of the Iraqi people (Ricks, 2006). The scandal was followed by the Marine Corps’s siege of Fallujah, further antagonizing Iraq’s Sunni population. On its heels was the fight against Moqtadr al-Sadr, hardening attitudes among the Shiites. As a result, “Operation Iraqi Freedom” became a barbaric guerrilla war and America became the hated occupier, thereby fulfilling (at least by all outer appearances) Samuel Huntington’s grim prediction about a “clash of civilizations” between the United States and Islam.

Despite their importance in the history of the Iraq war, the Abu Ghraib photos have been presented by the mass media in a piecemeal fashion—with little regard for the power of their visual content, and even less regard for how they may affect Muslim audiences around the world. In Torture and Truth, Mark Danner (2004: xiv) offers an antidote to this failing by arguing that Abu Ghraib “is not about uncovering what is hidden, it is about seeing what is already there—and acting on it.”

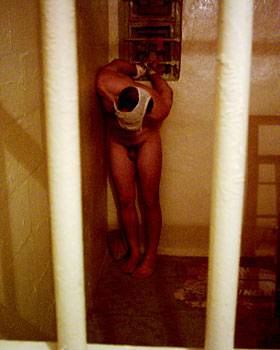

Scholars have met this challenge by offering fascinating sociological perspectives on Abu Ghraib (e.g., Apel, 2005; Brown, 2005; Ferrell, et al., 2005; Mestrovic, 2007), but few have examined the disgrace for what it really is: a crime. This is surprising given criminology’s traditional concerns with violent subcultures and prisoners’ rights. It is especially surprising that left-leaning criminologists have been generally silent on the subject. Consider, for example, how the following Abu Ghraib photograph might be reconciled with Foucault’s famous argument in Discipline and Punish (1977: 16) that modern societies are moving away from controlling the body of the prisoner through a “reduction in penal severity…[characterized by] less cruelty, less pain, more kindness, more respect, more humanity.”

In trials of the soldiers brought to justice for this crime, judges ruled that photographs are the “best evidence” in the public debate about the abuses of Iraqi prisoners by American soldiers at Abu Ghraib (Preston, 2005). So be it. This essay presents a collection of the photographs and makes two general points about them. First, a contemplative examination of the photos reveals that the suffering inside Abu Ghraib went far beyond the images of Private England and others humiliating the Iraqis under their control. In fact, the pictures constitute nothing less than the photographic record of a crime committed by the capitalist state. This was the high crime of torture—deliberate, systematic, brutal torture carried out by American soldiers with appalling shamelessness.

But they were not the ultimate perpetrators of this crime. The photographic record—along with supporting evidence from various investigations—reveals that the torturing of prisoners at Abu Ghraib followed directly from decisions by top officials, from President George W. Bush on down, to “take off the gloves” in prisoner interrogations. Although the policies and practices of the U.S. Central Intelligence Agency are almost entirely hidden from public view, available evidence—some of which is considered in this article—does indicate that the CIA was the lead agency at Abu Ghraib (with Army intelligence and military police in supporting roles). Therefore, the CIA is primarily responsible for what happened there—an aspect of the Abu Ghraib scandal that has been largely ignored by the media (Goodman and Goodman, 2006 are a rare exception).

In the second point made here, and contrary to Phillip Zimbardo’s infamous Stanford prison experiment, I argue that the enduring lesson of Abu Ghraib is that the human capacity for brutality is not universal; rather, group culture and organizational leadership are the catalysts that turn ordinary people into predators.

Foreground

The crimes of Abu Ghraib began in the late summer of 2003 against the backdrop of rising chaos in Iraq brought on by an insurgency for which the United Statesmilitary was woefully unprepared. At the time, several thousand civilians were incarcerated at the prison. Most had been rounded up in indiscriminate “cordon-and-sweep” operations primarily intended to humiliate Iraqi men and insult their personal dignity. The tactic was described by the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), following its visits to Abu Ghraib on September 12 and October 21, 2003.

Arresting authorities entered houses usually after dark, breaking down doors, waking up residents roughly, yelling orders, forcing family members into one room under military guard while searching the rest of the house and further breaking doors, cabinets and other property. They arrested suspects, tying their hands in the back with flexi-cuffs, hooding them, and taking them away. Sometimes they arrested all adult males present in a house, including elderly, handicapped and sick people. Treatment often included pushing people around, insulting, and taking aim with rifles, punching and kicking and striking with rifles. Individuals were often led away in whatever they happened to be wearing at the time of arrest—sometimes in pyjamas [sic]or underwear—and were denied the opportunity to gather a few essential belongings, such as clothing, hygiene items, medicine or eyeglasses (ICRC, 2004: 256).

The warden at Abu Ghriab, reserve Brigadier General Janis Karpinski, commander of the 800th Military Police (MP) Brigade, and the vast majority of the 300 MPs under her supervision, had never worked in a prison and therefore had no experience or training in the handling of inmates. By all accounts, Karpinski was considered grossly incompetent. She failed to provide both a system to process the detainees, and an adequate number of translators and interrogators to identify genuine insurgents among the thousands of innocent or neutral Iraqis caught up in the sweeps (Ricks, 2006; Taguba Report, 2004). Over the next several months hundreds of raids were conducted and the Abu Ghraib population swelled to more than 10,000 inmates, including women and children as young as nine years old (Kennedy, 2006). Some “high value” detainees arrived with broken bones from beatings; others were brought in severely burned from being strapped across the hoods of Army trucks as they were transported, tied down like slain deer (Ricks, 2006.).

As insurgents mounted nightly mortar attacks on the prison, MP units were placed on mandatory sixteen-hour shifts, often for seven days a week. They became demoralized and heavily outnumbered, with a prisoner-to-guard ratio of 75:1, overwhelming the institution’s security, food service, and sanitation systems. More than a hundred MPs themselves lived in cells at Abu Ghraib, often in total darkness due to the electrical blackouts in Baghdad. Wild dogs roamed the compound digging up bones from shallow graves. With the heat index at times reaching 130 degrees, the prison was beset with an overwhelming stench of sweat, feces, urine, and misery. MPs christened the place “Abu Ghetto” (Kennedy, 2006). Misconduct was rampant among the MPs and roughly 40 percent of them suffered from some kind of medical or psychological problem, ranging from severe dehydration and dysentery to post-traumatic stress disorders (Mestrovic, 2007; Taguba Report, 2004).

Against this perilous foreground military officials came under increasing pressure from Washington for “actionable intelligence” on the insurgency. For the top military commander in Iraq, Lieutenant General Ricardo Sanchez, this directive posed a dilemma with respect to the Abu Ghraib detainees. “There was never supposed to be a problem with detainees,” argues Thomas Ricks in Fiasco, his authoritative book on the Iraq war, “because there weren’t supposed to be any….The war plan had called for the Iraqi population to cheerfully greet the American liberators, quickly establish a new government, and wave farewell to the departing American troops” (2006:290-1). In reaction to this strategic predicament, on October 12 Sanchez approved nineteen new interrogation techniques to be used at the prison, including the use of stress positions, the forced removal of clothing, solitary confinement for up to 30 days, light deprivation, and prolonged exposure to loud noises (Schlesinger, 2004). These techniques had the full support of the Pentagon and President Bush (Hersh, 2005). “We had a policy that reflected the President’s policy,” Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld later recalled. “It went right down [the chain of command]” (U.S. Department of Defense, 2004).

Meanwhile, the CIA began to mobilize more and more of its resources out of Afghanistan and into Iraq to acquire intelligence on the insurgency, primarily from prisoners. The CIA teams brought their own practices with them (practices that would end up being used by both CIA officers and military intelligence), including various special interrogation techniques, the holding of prisoners without charging them, and the “extraordinary rendition” of detainees to countries that the U.S. State Department cites for torture or ill-treatment of prisoners, including Jordan, Syria, Egypt, Morocco, and Uzbekistan—where prisoners have actually been boiled to death (Grey, 2006; Risen, 2006). “Abu Ghraib in fall 2003 may have been its own particular hell,” writes Walsh (2006:4), “but the variations of individual abuse perpetrated there appear to be exceptional in only one way: They were photographed.”

The photographs were taken with digital cameras by MPs working the night shift inside cellblock 1, the so-called Hard Site—seven tiers of cells where interrogations took place—and later gathered by the Army’s Criminal Investigation Division (CID) (Hersh, 2005). (A section of the cellblock, 1 Alpha, housed high security CIA prisoners). The full dossier of the CID’s photographic evidence includes 16,000 photos (only 200 were made public), 173 of which were taken by Corporal Charles Graner, Jr., the ringleader of the abuse, and 112 videos. The archive depicts rampant mistreatment of prisoners including forced hooding and nudity, the use of dogs to terrorize detainees, forcing detainees to remain in stress positions for prolonged periods, and varieties of sleep deprivation.

Some of these techniques were designed by Sanchez’s point man on interrogations, Major General Geoffrey Miller—former head of the Guantanamo Bay detention center in Cuba (aka, Gitmo)—who was appointed to Abu Ghraib by Donald Rumsfeld in September 2003. Miller’s tactics were intended to “Gitmo-ize” Abu Ghraib by attacking cultural sensitivity, particularly male sensitivity to issues of gender and sexuality—a technique that Miller reportedly drew from cultural anthropologist Rapael Patai’s 1978 book The Arab Mind, which depicts sexual shame and humiliation as the greatest weakness of Arab men (Ibid.). In addition to attacking cultural sensitivity, Miller ordered physicians and psychologists to review inmate records, looking for individual phobias that could be used to exploit the inmates’ fears (Miles, 2006).

The techniques emerging from Miller’s Gitmo-ized model included beatings, starving, asphyxiation, burning, stretching (as in the medieval “rack”), sexual degradations, “low-voltage electrocution,” all manner of psychological manipulation, mutilation via dog bites, forced drugging, and forcing victims to watch the abuse of loved ones as a method of emotional blackmail (Marks, 2005; Miles, 2006; Ricks, 2006). Prisoners were raped, ridden, deprived of medical treatment, and forced to eat pork and drink alcohol in contravention of their religion (Buncombe et al., 2005). The abuse was pervasive and occurred in showers, stairwells, hallways, storage containers, and vehicles (Mestrovic, 2007). Cellblocks were filled with the screams of inmates. An Abu Ghraib detainee would later recall: “We suffered. We wept. We kept silent” (Kennedy, 2006).

In Miller’s words, the purpose of this was “to treat prisoners like dogs” (Karpinski, 2006), yet the Pentagon would later claim that there was resistance to Miller’s correctional philosophy. An Army investigation says, “There was a great deal of animosity on the part of the Abu Ghraib personnel, especially some [military intelligence] Personnel. This included an intentional disregard for the concepts and teachings the GTMO Team attempted to instill” (Fay, 2004: 59). Even so, no one in the military intelligence community had the courage to blow the whistle, and for good reason: Whistle-blowing would do no good because Miller’s tactics were part of an overarching doctrine of prisoner abuse sanctioned at the highest levels of the United States government.

Entries from a prison logbook contained within the CID archive indicate that in numerous cases MPs believed their tactics were being approved by—and in some cases ordered by—military intelligence officers, CIA agents, and private contractors (Walsh, 2006). Karpinski later claimed that military intelligence had given the MPs “ideas” that led to the abuse (Taguba Report, 2004). These tactics were not employed during interrogation sessions per se; rather, MPs were ordered to use them as a means of “softening up” detainees for questioning by CIA and military intelligence (Hersh, 2005; Schulz, 2005). Information gathered in the interrogations was to be funneled into a newly-established $11 million computerized database known as the Intelligence Fusion Center (Ricks, 2006). Yet little intelligence, actionable or otherwise, came from the Abu Ghraib prisoners.

Evidence of wrongdoing at Abu Ghraib first surfaced on December 12, 2003, when a confidential report by retired Army Colonel Stuart Herrington charged that prison officials were systematically violating the human rights of detainees under the Geneva Conventions. Though the date of Herrington’s report indicates that theU.S. government had access to knowledge of serious abuses four months before the photographs were leaked to the press, those abuses continued (Mestrovic, 2007). Then on February 24, 2004, the ICRC released its signature report to the Pentagon (the ICRC does not release reports to the press), stating: “In Abu Ghraib’s military intelligence section, methods of physical and psychological coercion used by the interrogators appeared to be part of the standard operating procedures by military intelligence personnel to obtain confessions and extract information” (2004:9). The report also documented the abuse of children at the prison and the rape of female detainees. Citing military intelligence officers, the Red Cross found that between 70 and 90 percent of persons deprived of their liberty in Iraq had been arrested by mistake. (The Army would later estimate that 85 to 90 percent of arriving Abu Ghraib prisoners either had no intelligence value or were outright innocent of terrorism-related charges [Fay, 2004]).

On the evening of April 28, 2004, a small portion of the Abu Ghraib photographs were shown on the CBS television program 60 Minutes II. Two days later the New Yorker magazine posted on its Web site a fuller account of the images. The pictures were then broadcast by CNN, the BBC, and Al-Jazeera, unleashing public horror and outrage around the world.

The U.S. Torture Paradigm

The Red Cross found that the methods of abuse at Abu Graib were “part of a process” deployed by U.S. interrogators on a daily basis at a series of overlapping CIA and Defense Department detention systems; first against a few high value al-Qaeda suspects at Bagram Air Base in Afghanistan, then against scores of ordinary Afghans and other Arabs at Guantanamo, and finally against hundreds of innocent Iraqis at Abu Ghraib and other military bases across Iraq—where the U.S. Army would document 26 confirmed prisoner deaths due to abuse (Physicians for Human Rights, 2005). Abu Ghraib was the tip of the iceberg. Practices at the prison represented a pattern of abusing inmates, not an isolated event. But did this “process” actually involve torture?

The 1985 United Nations Convention against Torture, ratified by the United States in 1994, defines torture as “Any act by which severe pain or suffering, whether physical or mental, is intentionally inflicted on a person for such purposes as obtaining from him or a third person information or a confession.” The Torture Convention also makes clear that “[n]o exceptional circumstances…may be invoked as a justification of torture.” Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions on prisoners of war contains similar language. The Article prohibits “violence to life and person, in particular murder of all kinds, mutilation, cruel treatment and torture.” Grave breaches to these international standards are called war crimes.

Throughout history, torturing societies have created laws and policies to authorize the practice. The United States is no different. Its first shot across the legal bow came in 2001 when Vice-President Dick Cheney, in an interview on Meet the Press, said that the government might have to go to “the dark side” in handling terrorist suspects, adding, “It’s going to be vital for us to use any means at our disposal.” As American military forces began to apprehend al-Qaeda and Taliban suspects on the battlefields of Afghanistan, Defense Department lawyers requested from the U.S. Justice Department a review of interrogation tactics that were permitted under both U.S. and international law. This led to a memorandum from Assistant Attorney General Jay S. Bybee to White House counsel Alberto Gonzales (to become the Attorney General of the United States in 2005). Based on Bybee’s legal review, Gonzales and associate John Yoo built a theory of torture which stipulated that in order for an act to rise to the level of torture within the meaning of both the UN and Geneva Conventions, “it must inflict pain that is difficult to endure. Physical pain amounting to torture must be equivalent in intensity to the pain accompanying serious physical injury, such as organ failure, impairment of bodily function, or even death” (Bybee, 2002:115, emphasis added).

On January 25, 2002, Gonzales espoused this theory in a memorandum to the President. Arguing for a “new paradigm” of interrogations, Gonzales declared that the war on terrorism “renders obsolete” the “strict limitations on questioning of enemy prisoners” required by the Geneva Conventions. Advising caution, however, Gonzales warned the President that the U.S. mistreatment of prisoners might be prosecutable under the War Crimes Act of 1996. On February 7, Bush issued a written order approving Gonzales’s review. Announcing that the war on terrorism had ushered in a new paradigm on prisoner interrogations, Bush wrote that the provisions of Geneva did not apply “to our conflict with al Qaeda.” Nevertheless, the President stipulated that all prisoners should be treated “humanely, and to the extent appropriate and consistent with military necessity, in a manner consistent with the principles” of the Geneva Conventions (Bush, 2002, emphasis added).

The CIA Test Case

From the beginning of the war on terrorism, top officials in the Bush administration recognized the need for a division of labor in its interrogations of the enemy. Accordingly, Army intelligence would take responsibility for interrogating the regular flow of people caught up in the sweeps, while the CIA would specialize in the handling of high value detainees. The practice of torture began in the latter domain.

The new paradigm of interrogations was first applied at a secret CIA safe house in Thailand during the spring of 2002. There, CIA agents had made little progress in questioning captured al-Qaeda operative Abu Zubaydah because he was heavily medicated on painkillers as a result of severe bullet wounds, including one in the groin, which Zubaydah had received during his arrest in Pakistan that January. According to journalist James Risen’s interview with a CIA official present at a White House briefing on the matter, President Bush took a “very personal interest in the Zubaydah case” (2006:22). Referring to Zubaydah, Risen’s source claims that Bush turned to CIA Director George Tenet and asked: “Who authorized putting him on pain medication?”

Was the president of the United States implicitly encouraging the director of Central Intelligence to order the harsh treatment of a prisoner? If so, this episode offers the most direct link yet between Bush and the harsh treatment of prisoners by both the CIA and the U.S. military. If Bush made the comment in order to push the CIA to get tough with Abu Zubaydah, he was doing so indirectly, without the paper trail that would have come from a written presidential authorization (Risen, 2006: 22.)

And so, according to another well-placed CIA source developed by journalist Ron Suskind: “He [Zubaydah] received the finest medical attention on the planet. We got him in very good health, so we could start to torture him” (2006:100). Based on the recommendations of CIA psychiatrists, Zubaydah was stripped and placed in a cell without a bed or blankets. He was forced to stand for hours on the bare floor, with air-conditioning adjusted so that he would turn blue, and exposed to deafening blasts of music by the Red Hot Chili Peppers (Johnston, 2006). “These procedures were designed to be safe, to comply with our laws, our Constitution and our treaty obligations,” Bush said of Zubaydah’s treatment (Ibid.).

Abu Zubaydah was a test case for the CIA’s evolving new role as jailhouse interrogator after September 11. “It was at this point,” recalled CIA Director Tenet of the Zubaydah case, “that we got into holding and interrogating high-value detainees…in a serious way” (2007: 241). Bush’s comment about pain medication for Zubaydah “made it clear to [CIA] officials in many ways that it was time for the gloves to come off,” Risen concludes (2006: 23). Suskind’s CIA source understood much the same. After 9/11, said the source, Bush had a way of pushing people “to do things they didn’t think they were capable of” (2006:101). Bush also had a way of pushing his lawyers to do things that would expand his executive powers to treat detainees harshly.

In August 2002, several months after the Zubaydah affair, the Justice Department’s Office of Legal Counsel, which acts as an in-house law firm for the President, sent a memo to the White House secretly authorizing the CIA to inflict pain and suffering on detainees during interrogations, up to the level caused by “organ failure” (Mayer, 2005). The memo stipulated that torture was illegal only when it could be proved that the interrogator intended to cause the required level of pain. This document—widely known as the “torture memo”—also advised that, under the legal doctrine of military necessity, the President could supersede national and international laws prohibiting torture.

Gonzales approved the torture memo, and with that the stage was set for Abu Ghraib. George W. Bush may never have issued a written policy or a direct order authorizing the torture of prisoners at the Baghdad prison. But Bush’s personal management style, combined with his approval of the torture memo, unleashed dozens of CIA agents to do what they had been trained to do.

Interrogation Policy at Abu Ghraib

As a practical matter, the new paradigm lacked coherence and ultimately it created great confusion among those responsible for its implementation. This became apparent in the aftermath of Saddam Hussein’s defeat in May 2003, and the subsequent cordon and sweep operations that filled Abu Ghraib with thousands of innocent Iraqis. In early October, the Justice Department issued an opinion stating that Iraqi insurgents were not protected by the Geneva Conventions. Weeks later the Department reversed itself, declaring that the Conventions did apply to prisoners in Iraq. However, non-Iraqi prisoners in Iraq were exempt from the moral standards of Geneva, as were detainees in Afghanistan and at Guantanamo. Because different rules applied to different prisoners in Iraq, and because many CIA and military intelligence officers in Iraq had just returned from Afghanistan where the Geneva Conventions were deemed obsolete, there was significant ambiguity about the rules of engagement at Abu Ghraib. Jeffrey Smith, former counsel for the CIA, later told a reporter: “Abu Ghraib has its roots at the top. I think this uncertainty about who was and who was not covered by the Geneva Conventions…bred the climate in which this kind of abuse takes place” (quoted in Mayer, 2005: 5). The Army’s investigation of Abu Ghraib similarly notes that neither “camp rules nor the provisions of the Geneva Conventions [were] posted in English or the language of the detainees” (Taguba Report, 2004:302). Referring to the Hard Site, an MP later recalled: “I never saw a set of rules…for that section. Just word of mouth…nothing was ever written down” (Ibid: 294).

Because of its imprecision, Bush’s new paradigm allowed for extremely harsh methods to be used against inmates at Abu Ghraib, thereby narrowing the definition of torture almost to the vanishing point. Amnesty International would later declare that Bush’s interrogation paradigm constituted the most significant attack on international law in fifty years, adding that the United States had condoned “atrocious” human rights violations, thereby diminishing its moral authority and setting a global example encouraging torture by other nations (Cowell, 2005; Schulz, 2005). Bush (2005a) dismissed these charges by claiming, “It seemed like to me they [Amnesty] based some of their decisions on the word of—and the allegations—by people who were held in detention, people who hate America, people that had been trained in some instances to disassemble—that means not tell the truth.”

For the inmates at Abu Ghraib, Bush’s policy meant that only severe pain or permanent physical damage—caused by procedures specifically intended to bring about such pain or physical damage—could be considered torture. Mere “cruel, inhuman, or degrading” treatment did not qualify; nor did “outrages upon personal dignity.” Therefore, any method of interrogation that fell short of “intentionally” inflicting pain tantamount to organ failure or death was legal under Bush’s powers as Commander-In-Chief (Yoo, 2006). Such provisions did not apply to private contractors employed by the CIA, however, because corporate mercenaries operated outside the U.S. chain of command and therefore were not subject to American justice systems (Ricks, 2006).

The Theories of Abu Ghraib

There are three theories about the torture scandal. Although an Army report concludes that there “is no single, simple explanation for why this abuse at Abu Ghraib happened,” (Jones, 2004:2) that is precisely what the military offers: a single, straightforward theory about the physical and sexual abuse of prisoners at Abu Ghraib. In this theory, supported by the Bush administration and its defenders, the abuse is attributed to a few “bad apples” among the military’s lower ranks. Insisting that its top commanders were not at fault, and that there was no policy, directive or doctrine allowing abuse, the Army pinned the entire affair on “a small group of morally corrupt soldiers and civilians” who had smeared the Army’s honor (Ibid.).

The “bad apples” were mainly low-ranking reservists of the 372nd MP Company; they included Lynndie England, her lover and supervisor at the time, Charles Graner, and Specialist Sabrina Harman. In the words of Donald Rumsfeld, the abuses at Abu Ghraib were “perpetrated by a small number of U.S. military” (quoted in McCoy, 2006a: 4). Cheney described the perpetrators as simply “rogue soldiers” (quoted in Curtiss, 2005: 30). To this day, the Bush administration defends the bad apple theory even though the Army’s report says that “twenty-seven Military Intelligence…Personnel allegedly requested, encouraged, condoned or solicited MP personnel to abuse detainees and/or participated in detainee abuse” (Jones, 2004:3, emphasis added).

The second theory is based on Zimbardo’s 1971 Stanford prison study in which two dozen college students were randomly selected to play the roles of prisoners or guards in a simulated prison setting. Believing that his experiment has striking similarities to the Abu Ghraib torture scandal, Zimbardo attributes the abuse to a collapse of discipline in an over-strapped and unsupervised military unit. Rather than blaming bad apples, Zimbardo (2004:1-2) reflects on his experiment to arrive at an explanation wherein “once-good apples [were] soured and corrupted by an evil barrel…[created by] the vinegar of needless war.” Like Dr. Jekyll turning into Mr. Hyde, good soldiers became bad soldiers because they were psychologically traumatized by war and the chronic, dysfunctional conditions inside Abu Ghraib. This profound social psychological transformation led to boredom among the MPs; which, in turn, caused them to exploit their power imbalance over inmates by turning them into “their playthings.” These amusements spun out of control, leading to the physical and sexual abuse of prisoners. Zimbardo argues that most of us would behave this way under similar circumstances. In other words, we are all latent torturers.

Proponents of Zimbardo’s “automatic brutality” theory often distinguish between psychological and physical abuse. In this argument, psychological abuse (referred to as “torture lite”) does not constitute torture, but physical pain does. Miles (2006), for example, limits his definition of torture to pain interrogation (and fixes blame for Abu Ghraib on unethical medical personnel who failed to challenge these practices). Such a torture paradigm is based on the assumption that a prisoner will tell the truth in order to escape a prolonged period of physical agony.

The third theory is advanced by the historian Alfred McCoy who argues that the tactics used at Abu Ghraib cannot be so easily categorized into physical and psychological dimensions. According to McCoy, over the years American military interrogators have found that mere physical pain, no matter how extreme, often produces heightened resistance in prisoners. Once this was understood, the CIA designed a revolutionary two-phase form of torture that fused sensory disorientationand self-inflicted pain. This combination causes victims to feel responsible for their suffering and thus capitulate more readily to their torturers. Through repeated practice in South Vietnam during the 1960s and Latin America in the 1980s, the CIA refined their tactics of sensory disorientation into a total assault on all senses and sensibilities—auditory, visual, temperature, sexual, and cultural. When merged with self-inflicted pain, these tactics create “a synergy of physical and psychological trauma whose sum is a hammer-blow to the fundamentals of personal identity” (McCoy, 2006b:8). McCoy contends that the abuses at Abu Ghraib were sanctioned by upper echelons of the U.S. government. Specifically, McCoy maintains that the CIA was, in fact, the lead agency at Abu Ghraib, enlisting Army intelligence to support its mission. An Army inquiry would later allude to such a theory, and parenthetically confirm Zimbardo’s perspective, by stating: “CIA detention and interrogation practices led to a loss of accountability, abuse…and an unhealthy mystique that further poisoned the atmosphere at Abu Ghraib” (Fay, 2004: 87). A report by the NewYork Times would likewise reveal that soldiers at Abu Ghraib had learned to use “stress techniques” in Afghanistan by “watching Central Intelligence Agency operatives interrogating prisoners” (cited in McCoy, 2006b:136).

The Context

These theories provide a basis for interpreting the Abu Ghraib photographs. The following photos were identified by Army investigators as instances of “intentional violent or sexual abuse” (Jones, 2004). The images are best understood in the context of cultural criminology (see Ferrell, 2007)—a criminology of everyday life which, in this case, necessarily concentrates on both the thrills of sexual violence experienced by the immediate perpetrators of the torture, as well as the agony suffered by victims. For the CID archive reveals that the torture and the sexual humiliation of prisoners were often performed in conjunction with American soldiers having sex with prisoners, and with each other.

At one point in the archive, MPs stand by as a detainee is seen sodomizing himself with a banana; at another point, Graner is sodomizing a 15-year-old boy with a phosphorescent light tube, as the boy screams for help. At another point, a dozen inmates are stacked in a naked pyramid; at another point, a male MP is having sex with a female inmate; at another point, a female MP is forcing inmates to masturbate one another; at another point, a male interrogator is sodomizing a boy; and at still another, Private England is on here knees giving Corporal Graner a blow job. There is, then, a pornographic function of the torture scenarios described below, providing what Jock Young (2007: 160) trenchantly calls “a photographic satire on bourgeois individualism worthy of the Marquis de Sade.”

The Evidence

Among the scenes photographed by Graner on October 18 and 19 (2003), dozens depict a single detainee shackled naked with underwear on his head. Graner told the CID that he was ordered by a “civilian contractor” (often a euphemism for CIA) to strip, shackle and hood the detainee as part of a sleep deprivation program (Danner, 2004). The detainee later told investigators:

They stripped me of all my clothes, even my underwear. They gave me woman’s underwear that was rose color with flowers in it, and they put the underwear over my face. One of them whispered in my ear, ‘Today I am going to fuck you,’ and he said this in Arabic.

I faced more harsh punishment from Grainer[sic]. He cuffed my hands with irons behind my back to the metal of the window, to the point my feet were off the ground and I was hanging there for about five hours just because I asked about the time, because I wanted to pray. And then they took all my clothes and he took the female underwear and he put it over my head. After he released me from the window, he tied me to my bed until before dawn….until I lost consciousness (Testimony of Hila, 2004).

Several conclusions can be drawn about the photo and accompanying text. First, although Miller’s Gitmo-ized interrogation methods allowed such short-shackling “for no more than 1 hour per use” (Schlesinger, 2004), this detainee was held five times as long in the first use, then an undetermined number of hours in the second use (“he tied me to my bed until before dawn”). Even within the wide-sweeping legal authority granted soldiers in the war on terrorism, Graner had gone over the top.

For the prisoner, the net physical effect of this treatment was excruciating.[1] After being made to stand barefooted on concrete for hours on end, fluids would have begun to flow down to the inmate’s legs. The legs would have then swollen, forming lesions that would erupt and separate, possibly leading to hallucinations. Then it is possible that the kidneys would have shut down. As the prisoner tired, he would have slouched forward. The weight of his arms pulling on the chest cavity would have constricted breathing, thereby compromising oxygen flow to the brain and other vital organs. Note that the pain is self-inflicted; it is not coming from the outside in the form of a beating or a cattle prod, but from within—driven by the prisoner’s weakness to help himself.

Second, the treatment was also designed leave the prisoner in a state of acute psychological trauma. The prisoner’s nakedness and the use of women’s underwear were meant to sexually humiliate him. Along with the threat of homosexual rape (“Today I am going to fuck you,”), the abuse constitutes an assault on cultural prohibitions against homosexuality among Arabs and a cold-blooded attack on the inmate’s manhood. Such violence takes on added meaning when we consider that the inmate is being sleep deprived and sensually deprived of auditory and visual acuities. Following their visits to Abu Ghraib, Red Cross medical staff determined that prisoners so treated were suffering from “memory problems, verbal expression difficulties, incoherent speech, acute anxiety reactions, and suicidal tendencies” (ICRC, 2004: 13).

Put simply, this prisoner is being treated in a way that is “difficult to endure” because his “bodily functions are impaired.” Granier’s blatant violation of the Army’s short-shackling policy indicates that he “intended” to cause this level of pain and suffering. The abuse therefore constitutes an act of torture as torture is legally defined by the Bush administration itself.

According to the government’s theory, Graner concocted these torture techniques on his own. He was a very bad apple. According to Zimbardo’s theory, Graner was driven to the psychological brink by the social dysfunction of Abu Ghraib. How he acquired the torture techniques, the theory does not say. According McCoy’s theory, Graner was following CIA orders to abide by a precise set of practices designed for use on Arab men. Indeed, during his court martial Graner’s primary defense would be that the CIA and “other civilians” had wanted him to soften up prisoners to make them easier to interrogate (Curtiss, 2005). This is confirmed by a comment Graner made to a fellow MP at Abu Ghraib in October 2003. “MI [Military Intelligence] and OGA [Other Government Agencies, another euphemism for CIA] are making me do things that are morally and ethically wrong,” said Graner. “But I have no choice” (quoted in Kennedy, 2006). Graner’s superiors did not intervene to stop his sadistic treatment of inmates. Instead, in early 2004 Graner received an Army accommodation medal for his outstanding performance on the Hard Site (Ibid.).

Here is the last, and perhaps the most important point about the photograph presented above. According to the Army’s investigation (Fay, 2004), we can be 85-90 percent certain that this inmate had no intelligence value whatsoever. The investigation says: “Most…of the violent or sexual abuses occurred separately from scheduled interrogations and did not focus on persons held for intelligence purposes” (Jones, 2004:3, emphasis added). In other words, the torture of this prisoner failed to produce any intelligence because there was no intelligence to produce. Wildly contrary to President Bush’s stance on interrogations, the inmate posed no threat to the United States. He did not “hate America” nor was he trained to “disassemble” the truth. He was tortured for nothing.

The Pattern of Torture

One case does not an argument make, of course, so more evidence is necessary to either confirm or refute the various theories of Abu Ghraib. Such evidence is presented next. While the photos may have no corollary in the criminology literature, the following images indicate that there are corollaries within the Abu Ghraib photos themselves. That is, the images reveal a pattern of torture.

According to Graner’s testimony, after he and Sabrina Harman reported to work on the evening of November 4, Graner noticed an odd fluid leaking out of the showers into his office. Upon entering the shower room, the MPs spotted a sealed body bag leaking fluid across the floor. Inside they found a dead Iraqi packed in ice and decided to pose for pictures. In the photo above, Harman is grinning and giving a thumbs-up sign above the Iraqi’s mutilated face. “It was just a dead guy,” Harman said flatly of the incident. “No big deal” (quoted in Kennedy, 2006). The next morning, the dead man had an intravenous drip inserted into his arm and was carried out of the prison on a stretcher, so that other inmates would not realize he was dead.

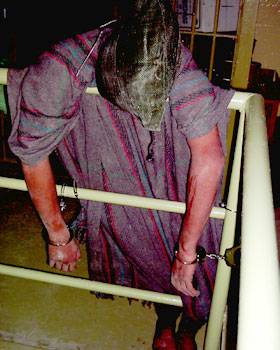

The dead prisoner was Manadel al-Jamadi, later to become known among troops as the “Ice Man.” He had been in CIA custody since his arrest at 2:00 a.m., November 4, by a Navy SEAL team which suspected him of involvement in a bomb attack against the Red Cross headquarters in Baghdad on October 27. Jamadi was a CIA “ghost detainee”—meaning he was arrested without charge and held in secret without access to Red Cross services as required by the Geneva Conventions (Grey, 2006). Upon his arrival at Abu Ghraib at 4:30 a.m., Jamadi was naked below the waist. A green plastic sandbag covered his head and plastic cuffs tightly bound his wrists. Due to a beating he received during his arrest—the SEALs had taken turns punching, kicking and poking Jamadi with their rifle butts while he was cuffed and hooded—Jamadi had six broken ribs (Cloud, 2005). Two CIA agents took Jamadi to a shower room on 1 Alpha where the agents ordered an MP to handcuff Jamadi behind his back and attach the cuffs to a barred window in the shower room in preparation for interrogation. “They used two pair of handcuffs and secured Al-Jamaidi [sic] in a standing position with his arms over and behind his head,” said a CIA report (quoted in Scherer and Benjamin, 2006). Before agents were able to get any information out of Jamadi, however, Jamadi’s knees buckled, putting all his weight on his hands, wrists, and rib muscles. An MP later recalled that he was surprised that Jamadi’s arms “didn’t pop out of their sockets” (Ibid.) Jamadi died within the hour. Pathologists ruled his death a homicide caused by “compromised respiration” due to the combination of broken ribs and the painful position in which he was suspended (Grey, 2006). Jamadi had been treated in a way that was “difficult to endure.” His “bodily functions” had been impaired to the point of death.

Hence there is parallel to the first torture scenario. Both prisoners were suspended by the wrists, with arms hyper-extended behind their backs—a position widely known as the “Palestinian hanging” for its alleged use by Israeli intelligence in the Palestinian territories. The stress position has been condemned by international human rights groups as torture. Human rights workers suspect that it was an “enhanced interrogation technique” approved by the Bush administration (Hettena, 2005).

Further evidence of the pattern appears in the photo above. Readers are well-aware of this image, also taken on the night of November 4. The prisoner is perched on top of a cardboard box; arms outstretched, with a hood on his head, a blanket around his shoulders and electrical wires extending from his hands. The hooded man was for many Arabs a shocking figure uniting humiliation and divinity. For Americans, not only did the photo represent the nation’s drift away from the ideals that made it for many a moral beacon in the post-World War II era, but it carried a postmodern burden as well: the burden of shame. The New York Times proclaimed that this image has “become in many eyes more the symbol of America than the Statue of Liberty” (Herbert, 2005).

To the MPs of Abu Ghraib, this prisoner was known as “Gilligan”—a reference to the television comedy character which epitomized the American effort to infantilize Arab men. He was handled primarily by Sabrina Harman, a 26-year-old Army reservist and former assistant manager at a Papa John’s Pizza in Lorton, Virginia. Harman had no prison guard experience and received virtually no training before starting her assignment on the Hard Site on October 18. Nevertheless, it was Harman’s job to keep Gilligan awake during his sleep deprivation. According to the testimony of the victim, Abdou Hussain Saad Faleh (Gilligan), a “tall black man” attached the wires to his fingers, toes, and penis—leaving him trembling, shaking, and afraid he was going to be killed (Testimony in Fay, 2004:77). “I was joking with him,” Harman said later, “and told him if he fell off, he would get electrocuted” (Testimony in Scherer and Benjamin, 2006.).

The bad apple theory holds that Harman dreamed this treatment up herself—that this untrained, lowly Army reservist, who had worked on the Hard Site for little more than two weeks, had the martial aptitude necessary to invent such cruelty. Again, Zimbardo’ theory offers no explanation for how Harman learned the technique. And McCoy’s theory says that the treatment is a CIA tactic, similar to the Palestinian hanging, in which sensory disorientation is fused with self-inflicted pain. Further insight is revealed below.

This is what happened to Gilligan before the iconic image was taken. According to Graner, on November 2 he was approached by a soldier from the Army’s CID—the same agency that would later investigate the Abu Ghraib scandal—and ordered to soften up Gilligan by making his life “a living hell for the next three days.” In the photo, Gilligan is hooded and handcuffed to a waist-high rail on a prison catwalk, his arms covered in blood. He remained in this stress position for three days, as Graner and a CID officer yelled at him, day and night, repeating lines from Stanley Kubrick’s apocalyptic 1987 film on the contradictions of the Vietnam war, Full MetalJacket. “It was basically…Full Metal Jacket—loud as you could to him, and then asking him what his name was,” Graner told investigators. “You fell asleep, you fell down. Wow, you just woke yourself up,” he explained (quoted in Scherer and Benjamin, 2006).

After being short-shackled to the rail for 72 hours, it is likely that Gilligan’s legs would have swollen, compromising his kidneys and other vital organs. Again the technique involves self-inflicted pain combined with sensory disorientation. And again, even though Gilligan was suspected of having information about the location of four missing U.S. soldiers, the Army could find no proof of that. Because Gilligan was deemed a model prisoner (Mestrovic, 2007), he was allowed to go free after Graner was done torturing him.

Here, finally, is Sabrina Harman as she appeared at the height of the Abu Ghraib ordeal. She appears to be wearing panties similar to those that were worn by an inmate who was tortured by Palestinian hanging outside his cell on November 29 (not shown here for legal reasons). Such behavior is consistent with a pattern of treatment involving the degradation of Arab men by female soldiers at Abu Ghraib. Only here, in this case, the ritualized humiliation of a prisoner is literally connected to the sexual seduction of his female captor. The bad apple theory suggests that Harman is smiling because she is simply happy to be wearing her panties on the outside of her military uniform, in the middle of a maximum security prison, inside a war zone. But a cleaner eye prevails. Sabrina Harman is not just smiling; she is in a state of unremitting joy. Though closed in bliss, even her eyes seem to be smiling. This poses no problem for the bad apple theory (bad apples can enjoy their sadism) but it does create problems for Zimbardo. Inspect the photo: Which seems more likely? Is this the look of a bored, stressed-out soldier trapped in a descending spiral of victimization brought on by the pressure to conform to the demands of a chaotic and overcrowded prison? Or, is this the look of a satisfied employee who has just performed her assignments precisely as she has been ordered by her male superiors?

Here, finally, is Sabrina Harman as she appeared at the height of the Abu Ghraib ordeal. She appears to be wearing panties similar to those that were worn by an inmate who was tortured by Palestinian hanging outside his cell on November 29 (not shown here for legal reasons). Such behavior is consistent with a pattern of treatment involving the degradation of Arab men by female soldiers at Abu Ghraib. Only here, in this case, the ritualized humiliation of a prisoner is literally connected to the sexual seduction of his female captor. The bad apple theory suggests that Harman is smiling because she is simply happy to be wearing her panties on the outside of her military uniform, in the middle of a maximum security prison, inside a war zone. But a cleaner eye prevails. Sabrina Harman is not just smiling; she is in a state of unremitting joy. Though closed in bliss, even her eyes seem to be smiling. This poses no problem for the bad apple theory (bad apples can enjoy their sadism) but it does create problems for Zimbardo. Inspect the photo: Which seems more likely? Is this the look of a bored, stressed-out soldier trapped in a descending spiral of victimization brought on by the pressure to conform to the demands of a chaotic and overcrowded prison? Or, is this the look of a satisfied employee who has just performed her assignments precisely as she has been ordered by her male superiors?

Conclusion: The Criminology of Torture

On April 20, 2004, George W. Bush stood before a crowd of supporters in Buffalo, New York, and declared that Iraq was moving from “torture and rape rooms to freedom” (Bush, 2004a). The Abu Ghraib photos were released eight days later, providing startling evidence that little had changed in Iraq since the fall of Saddam Hussein. “Let me make very clear the position of my government and our country,” said Bush in his official denial of responsibility for the mistreatment of Iraqis at Abu Ghraib. “We do not condone torture. I have never ordered torture. I will never order torture. The values of this country are such that torture is not part of our soul and our being” (quoted in Risen, 2006:24). In an earlier press conference, Bush blamed the abuse on “the actions of [a] few people” and promised a full investigation. “We’re a society that is willing to investigate, fully investigate in this case, what took place in that prison” (Bush, 2004b).

Five major investigations would follow. Despite Bush’s promises, none of them fully investigated the links between military police, military intelligence, the CIA, senior commanders in Iraq, the Pentagon and, finally, the White House. Nor did they fully investigate the atmosphere of legal ambiguity created by Bush’s policy decisions on the treatment of detainees in the war on terrorism. In an odd way, the sensational nature of the sexual abuse photos at Abu Ghraib became a diversion for violations of the Geneva Conventions that occurred there. None of the investigations even mentioned the reasons for detaining women and children at the prison. More the pity, there was little public outcry for a complete, independent inquiry and Abu Ghraib was dismissed as “Animal House on the night shift,” as former Defense Secretary James Schlesinger put it in his report. Abu Ghraib was simply the unauthorized actions taken by a few bad apples, coupled with the failure of a few leaders to provide adequate leadership.

Criminology has much to offer public conversations about Abu Ghraib. For starters, Bush’s renunciation of torture represents a classic state of denial, to use Stan Cohen’s piercing expression. Disavowals of torture “are not private states of mind,” argues Cohen. “They are embedded in popular culture, banal language codes and state-encouraged legitimations” (2001:76). Like Cohen’s description of torture committed by the Argentinean junta of the 1970s, the public discourse surrounding Abu Ghraib was highly coded and full of sanctimonious statements about national purity, good and evil, and the sacred responsibility to eliminate enemies. These statements formed the basis of the Bush administration’s denial text about Abu Ghaib. Rigid language rules, intended to conceal information, all but eliminated from the official discourse such concrete facts as those presented in this research; namely, that innocent prisoners were tortured at Abu Ghraib. Instead, the official discourse referred to “detainees” who had been “maltreated” and “abused” by “a few bad apples” in the “Animal House”—all of which was an unfortunate but minor concern in the “crusade” to rid the world of “evil-doers,” thus spreading “freedom and democracy” throughout the Middle East.

Moreover, Bush’s interpretive denial (Bush would claim on numerous occasions over the years that what happened at Abu Ghraib was really something other than torture) amounted to conscious disinformation intended to swindle the American public into thinking that the government’s investigations should be taken at face value, in the hope that the media—and by implication, the nation—would move on. The strategy was enormously successful inasmuch as the core problems of Abu Ghraib were never confronted and no independent commission was ever set up to investigate the policies that led to the torture. The Bush White House repudiated its torture memo in December 2004 (a few days before Alberto Gonzales’s confirmation hearings to become attorney general) and sidestepped all questions about authorizing the CIA to use harsh interrogation techniques. “It was as if the interrogation policies were developed in a presidential vacuum” laments Risen (2006:24). As a result, Abu Ghraib disappeared from the headlines, mainly because of the lack of proof that Bush had ordered the torture. Worse than torture not being in the news, it was no longer news.

High Crimes and Misdemeanors

Two years after his official denial, to his credit Bush proposed to demolish Abu Ghraib as a goodwill gesture to the Iraqi people. Blowing up the prison, bulldozing its remains underground, and allowing al-Jazzera to broadcast these scenes would have sent the Arab world a powerful message about America’s repentance for the sins of Abu Ghraib. Ironically, an American military judge ordered that the prison be preserved as a crime scene (Worth, 2006). A potentially significant political stride in America’s fight against terrorism’s global criminal threat—reducing the bitter anger that is now spreading across the Muslim world like wildfire—was itself usurped by crimes committed by the United States of America under the Presidency of George W. Bush.

Under the U.S. Constitution, a president can be impeached for “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Impeachable offenses include using lies and deceptions to formulate government policy, and deliberately violating laws of the United States. Under the War Crimes Act of 1996 it is a crime for any U.S. national to order or engage in the murder, torture, or inhuman treatment of a prisoner. Anyone in the chain of command who condones these crimes rather than stopping them could also be in violation of the Act. The Geneva Conventions also outlaws torture and murder; a recent landmark Supreme Court decision has rejected Bush’s assertion of broad executive powers, ruling that the Conventions are the law of the land and do apply to the treatment of detainees in the war on terrorism. Even within the administration’s own narrow legal definition, the foregoing photographic study shows that torture did occur at Abu Ghraib. To the extent that this torture took place as a result of the President’s policies or conduct, then George W. Bush may have violated both the War Crimes Act and the Geneva Conventions, and is therefore culpable of high crimes and misdemeanors.

Cohen argues that torture cannot be explained in the same way as ordinary crime, though he does allow that criminological theory may provide a framework for conceptualizing the problem. In this regard, and well-known to criminologists of all stripes, Edwin Sutherland (1947) maintained that all criminal behavior is learned, and that it is learned in interaction with others in a process of interpersonal communication. This learning process involves two characteristics: techniques of committing the crime—skill, or criminal tradecraft—which can sometimes be very complicated; and ideology, or the specific motives for the offense. Sutherland’s theory of ordinary transgressions offers insight into the problem of high crimes and misdemeanors.

No one is more responsible for spreading the ideology that America’s “enemies” are truly evil than George W. Bush. In so doing, Bush made it nearly impossible for MPs at Abu Ghraib to treat prisoners “humanely” because Bush’s ideology denied the humanity of these prisoners. This dehumanization process depended in large part on Bush’s post-9/11 constructing of Arabs and Muslims and terrorists as an undifferentiated mass, thereby making them far easier to humiliate, torture, and kill. As Stanley Milgram (1964) famously discovered more than forty years ago, a key condition for suspending human morality is an acceptable ideology for following an authority figures’ orders. Bush’s strident ideology allowed MPs like Charles Graner to overcome their innate revulsions to torture, and believe that they were operating in accord with the dominant public policy discourse. The duty to torture overrode moral absolutes not to torture. This had less to do with rogue soldiers or dysfunctional prison conditions than it did with an organizational leadership that demonstrated a moral vagueness toward the humane treatment of Arab prisoners. Why else would Graner receive an Army accommodation for his “work” at Abu Ghraib?

But the real utility of Sutherland’s theory is in its first principle. How did the MPs learn to torture? My research suggests that McCoy has it right. That is, while some instances of torture (e.g., rapes and beatings) were undoubtedly carried out by bad apples, and other times were perpetrated by soldiers working through a “diffusion of responsibility” problem as noted by Zimbardo in his automatic brutality theory, I argue that the most refined and aggressive interrogation methods used at Abu Ghraib were designed by the CIA. CIA field officers worked in close proximity to military interrogators at Abu Ghraib (McKelvey, 2007); and by virtue of that proximity, MPs were trained and ordered by CIA—often via military intelligence or private contractors—to use these aggressive methods against prisoners, and use them ruthlessly. Lynndie England, who worked at a West Virginia chicken-processing plant before her deployment to Iraq, did not possess the criminal tradecraft necessary to think up such things as the naked pyramid or the Palestinian hanging. What happened at Abu Ghraib was more sophisticated—so sophisticated, in fact, that its evil was masked from immediate perpetrators.

This was especially so for the women. Although they took the brunt of the blame for Abu Ghraib, Lynndie England and Sabrina Harman had no idea how their behavior fit into a larger picture. During their courts-marshal, it was determined that both women suffered from personal problems. Harman suffered from depression, dependency, anxiety attacks, and post-traumatic stress disorder, making her an extreme follower of someone who could help her. England suffered from depression and a language dysfunction that left her confused most of the time, thereby causing her to comply in the presence of authority figures (Mestrovic, 2007). Both women took their orders from Graner and Graner took his orders from the CIA or its intermediaries (it was through these channels that Graner received training in the use of stress positions and the Palestinian hanging [McKelvey, 2007]). Because England and Harman had no real intention of torturing prisoners—indeed, they couldn’t tell you the meaning of torture because neither received Geneva Conventions training—they became perfect foils for the CIA. Under American and international law, intent is central to assessing criminality in torture cases (Meyer, 2005). England and Harman had no intent, but they did have their sexuality. And this the CIA used to create a culture inside Abu Ghraib that exploited and debased women soldiers by having them behave like trollops. “The seductions of humiliation, particularly by those who themselves have been socially subordinate,” Young argues, “has been noted before in wartime and genocidal situations as well as in violent crime” (2007: 161).

The CIA Director at the time of the Abu Ghraib torture scandal, George Tenet, reported directly to the President of the United States. The chain of command between the President and the CIA is not complicated. According to Risen, no other American president in post-World War II history has met more often with his CIA Director than George W. Bush. Bush and Tenet spent hours together and developed a personal relationship. It is conceivable that through their interpersonal communication, if we are listening to Sutherland’s angel, Bush may have learned the word “disassemble” and came to believe that withholding pain medication from a high-value CIA detainee might lead to something useful. Senator Richard Durbin, who served on the Senate Intelligence Committee at the time, recalls: “Something significant was happening at the highest levels of the government when it came to torture policy” (quoted in Mayer, 2005: 11). This was confirmed by General Antonio Taguba, author of the original Army report on Abu Ghraib. “There was no doubt in my mind,” said the General upon his retirement, “that this stuff”—the explicit images—“was gravitating upward. It was standard operating procedure to assume that this had to go higher. The President had to be aware of this” (quoted in Hersh, 2007:11).

Anytime the CIA is involved in state criminality, of course, it will use what the agency calls a “cut out”—a person or persons who will provide plausible deniability for the President’s wrongdoing. “Bush made it clear to Tenet what he wanted done [in prisoner interrogations],” says Risen.

[But] it appears that there was a secret agreement among very senior administration officials to insulate Bush and to give him deniability, even as his vice president [Dick Cheney]…[was] meeting to discuss the harsh new interrogation methods with George Tenet (Risen, 2006:25).

Yet in the final analysis, this is a story about monumental administrative incompetence. Abu Ghraib was not an aberration. It was a symptom of a war in which the people in charge had no idea what they were doing. American efforts to rebuild looted schools and hospitals in Iraq, restore electricity and banking systems, train Iraqi police, and provide basic security have all been calamitous failures (Chandrasekaran, 2006). And so was the policy to extract confessions from inmates at Abu Ghraib by torturing them. Torture has utility for the state only when it induces useful information from the tortured; otherwise, you are torturing people for the hell of it. At Abu Ghraib, torture was used on innocent people who had no such information. “The Americans brought electricity up my ass before they brought it to my house,” mourned one of these innocents (Testimony in Walsh, 2006:7). Moreover, Abu Ghraib was apiece with a massive pattern of governmental failure in Iraq.

Not only have Bush’s catastrophic policy failures created a failed state in the middle of the Arab world; they have also undermined American legitimacy at home. “Our enemies are innovative and resourceful, and so are we,” said Bush upon signing a $402 billion Defense Department budget on August 4, 2005. “They never stop thinking about new ways to harm our country, and neither do we” (2005b). Bush’s malapropism speaks volumes about the consequences of his haphazard, ineffective, and morally hideous counterterrorism regime. “I’m also not very analytical,” said the 43rd President of the United States just days before MPs began to systematically strip Iraqis of their human dignity at Abu Ghraib. “I don’t spend a lot of time thinking about myself, about why I do things” (Bush, 2003).

Military records show that between 2004 and 2006 at least 19,000 Iraqis were released from Abu Ghraib and other military prisons in Iraq (Quinn, 2006). Nearly all were men who had nothing to do with terrorism. We will never know how many Iraqi men were tortured by American forces at Abu Ghraib, though it was certainly hundreds, if not thousands: All for nothing. But of this we can be sure: Once freed from prison, some of these men joined the insurgency, some joined death squads, and others became straight-up al-Qaeda (Hamm, 2007; Richardson, 2006).

References

Apel, D. (2005) “Torture Culture: Lynching Photographs and the Images of Abu Ghraib.” Art Journal. Summer: 88-100.

Brown, M. (2005) “’Setting the Conditions’ for Abu Ghraib: The Prison Nation Abroad.” American Quarterly, 57: 976-999.

Buncombe, A., Huggler, J. and L. Doyle (2005) “Abu Ghraib: Inmates Raped, Ridden Like Animals, and Forced to Eat Pork.” The Independent. April 21. (Internet version)

Bush, G.W. (2005a) President’s Press Conference, May 31. White House transcript.

_________ (2005b) President’s Address at the Signing of the Defense Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2005. Washington, D.C., August 4.

__________ (2004a) President’s Remarks in a Conversation on the USA Patriot Act, Buffalo, New York, April 20. White House transcript.

__________ (2004b) Transcript of George W. Bush’s Interview with Alhurra Television, May 5.

__________ (2003) Roundtable Interview of the President by White House Press Pool. June 4.

_________ (2002) Memorandum for the Vice President (et al.) Reprinted in Danner, pp. 105-6.

Bybee, J.S. (2002) Memorandum for Alberto R. Gonzales, Counsel to the President. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Legal Counsel (August 1). Reprinted in Danner, pp. 115-166.

Carter, P. (2004) “The Road to Abu Ghraib: The Biggest Scandal of the Bush Administration Began at the Top.” Washington Monthly, November. (Internet version.)

Chandrasekaran, R. (2006) Imperial Life in the Emerald City: Inside Iraq’s Green Zone. New York: Knopf.

Cloud, D. S. (2005) “Seal Officer Hears Charges in Court-Martial in Iraqi’s Death.” New York Times, May 25.

Cohen, S. (2001) States of Denial: Knowing About Atrocities and Suffering. Cambridge, UK: Polity.

Cowell, A. (2005) “U.S. ‘Thumbs Its Nose’ at Rights, Amnesty Says.” New York Times, May 24.

Curtiss, R. H. (2005) “The Midnight Shift at Abu Ghraib.” The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs, 24: 28-30.

Danner, M. (2004) Torture and Truth: America, Abu Ghraib, and the War on Terror. New York: New York Review Books.

Fay, G. R. (2004) Investigation of the Abu Ghraib Detention Facility and 205th MI Brigade. United States Army (Unclassified Report, Aug. 23).

Ferrell, J. (2007) “For a Ruthless Cultural Criticism of Everything Existing.” Crime, Media, Culture, 3: 91-100.

Ferrell, J., Greer, C. and Y. Jewkes (2005) “Hip Hop Graffiti, Mexican Murals and the War on Terror.” Crime, Media, Culture, 1: 5-9.

Foucault, M. (1977) Discipline and Punish (trans. A. Sheridan). New York: Vintage Books.

Goodman, A. and D. Goodman (2006) Static: Government Liars, Media Cheerleaders, and the People Who Fight Back. New York: Hyperion.

Grey, S. (2006) Ghost Plane: The True Story of the CIA Torture Program. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Hamm, M.S. (2007) Terrorism as Crime: From Oklahoma City to Al-Qaeda and Beyond. New York: New York University Press.

Hersh, S. M. (2007) “The General’s Report.” The New Yorker, June 25. (Internet version)

__________ (2005) Chain of Command: The Road from 9/11 to Abu Ghraib. New York: Harper Perennial.

Herbert, B. (2007) “The Real Patriots.” New York Times, February 19.

Hettena, S. (2005) “Reports Detail Abu Ghraib Prison Death.” Associated Press, Feb. 17.

Hila, Kasim Mehaddi (2004) Sworn Testimony of Kasim Mehaddi Hila. Available at Washingtonpost.com.

Johnston, D. (2006) “In Remote Prison, Disputes Flared Over Interrogations.” New York Times, September 10.

International Committee of the Red Cross (2004) Report of the ICRC on the Treatment by the Coalition Forces of Prisoners of War and Other Protected Persons by the Geneva Conventions in Iraq During Arrest, Internment and Interrogation. Reprinted in Danner, 251-275.

Jones, A.R. (2004) Executive Summary: Investigation of Intelligence Activities at Abu Ghraib. United States Army (Unclassified Report, Aug. 23).

Karpinski, J. (2006) Interview in Kennedy.

Kennedy, R. (2006) The Ghosts of Abu Ghraib. HBO Documentary Films. A Moxie Firecracker Production.

Marks, J. H. “Doctors of Interrogation.” The Hastings Center Report, 35: 17-24.

Mayer, J. (2005) “Can the C.I.A. Legally Kill a Prisoner?” The New Yorker, November 7 (Internet version).

McCoy, A. W. (2006a) “The Hidden History of CIA Torture.” Tomdispatch.com.

___________ (2006b) A Question of Torture: CIA Interrogation, from the Cold War to the War on Terror. New York: Metropolitan Books.

McKelvey, T. (2007) Monstering: Inside America’s Policy of Secret Interrogations and Torture in the Terror War. New York: Carroll & Graf.

Mestrovic, S. G. (2007) The Trials of Abu Ghraib: An Expert Witness Account of Shame and Honor. Boulder, CO: Paradigm Publishers.

Miles, S. H (2006) Oath Betrayed: Torture, Medical Complicity, and the War on Terror. New York: Random House.

Millgram, S. (1964) “Group Pressure and Action against a Person.” Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 9: 137-143.

Physicians for Human Rights (2005) Break Them Down: Systematic Use of Psychological Torture by US Forces. Cambridge, MA: Physicians for Human Rights.

Preston, J. (2005) “Judge Says U.S. Must Release Prison Photos.” New York Times, July 12.

Quinn, P. (2006) “In American Hands: Wartime Prisons.” Associated Press, October 1.

Richardson, L. (2006) What Terrorists Want: Understanding the Enemy, Containing the Threat. New York: Random House.

Ricks, T. E. (2006) Fiasco: The American Military Adventure in Iraq. New York: Penguin.

Risen, J. (2006) State of War: The Secret History of the CIA and the Bush Administration. New York: Free Press.

Scherer, M. and M. Benjamin (2006) “The Abu Ghraib Files.” Salon.com News.

Schlesinger, J. R. (2004) Final Report of the Independent Panel to Review DoD Detention Operations. U.S. Department of Defense.

Schulz, W. F. (2005) Annual Report. Amnesty International USA. May 25.

Suskind, R. (2006) The One Percent Doctrine: Deep Inside America’s Pursuit of Its Enemies Since 9/11. New York: Simon & Schuster.

Sutherland, E. (1947) Criminology. Philadelphia: Lippincott.

Taguba Report (2004) Article 15-6 Investigation of the 800th Military Police Brigade. U. S. Department of Defense. Reprinted in Danner, 2004, pp. 279-328.

Tenet, G. (2007) At the Center of the Storm: My Years at the CIA. New York: HarperCollins.

United States Department of Defense (2004) Pentagon Operational Update Briefing. May 4.

Walsh, J. (2006) “Abu Ghraib Photos and Videos.” Salon, March 13.

Worth R. F. (2006) “U.S. to Abandon Abu Ghraib and Move Prisoners to a New Center.” New York Times, March 10.

Yoo, J. (2005) “Behind the ‘Torture Memos.’” CFIF.org, Dec. 6.

Young, J. (2007) The Vertigo of Late Modernity. Los Angeles: Sage.

Zimbardo, P. G. (2004) “Power Turns Good Soldiers into ‘Bad Apples.’” Boston Globe, May 9.

[1] The following description is based on expert medial opinions in Mayer, 2005 and McCoy, 2006b, as well as from medical professionals interviewed for thisresearch.